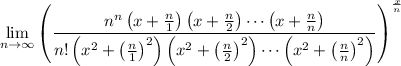

Use the old exp-log trick and properties of the logarithm to rewrite the limit as

![\displaystyle = \exp\left[\lim_(n\to\infty) \frac xn \ln \left((n^n \left(x+\frac n1\right) \left(x+\frac n2\right) \cdots \left(x+\frac nn\right))/(n! \left(x^2+\left(\frac n1\right)^2\right) \left(x^2+\left(\frac n2\right)^2\right) \cdots \left(x^2+\left(\frac nn\right)^2\right))\right)\right]](https://img.qammunity.org/2023/formulas/mathematics/college/o37vsl47v5qbw5v5ifq6nq3zggaa022tol.png)

![\displaystyle = \exp\left[x \lim_(n\to\infty)\frac1n\ln\left((n^n)/(n!)\right) + \frac1n \sum_(k=1)^n \ln\left(x+\frac nk\right) - \frac1n \sum_(k=1)^n \ln\left(x^2+\left(\frac nk\right)^2\right)\right]](https://img.qammunity.org/2023/formulas/mathematics/college/nau7nzdkicda884pqxe9k7oddrlaiovf2k.png)

![\displaystyle = \exp\left[x \lim_(n\to\infty)\frac1n\ln\left((n^n)/(n!)\right) + \frac1n \sum_(k=1)^n \ln\left(x+\frac1{k/n}\right) - \frac1n \sum_(k=1)^n \ln\left(x^2+\frac1{\left(k/n\right)^2}\right)\right]](https://img.qammunity.org/2023/formulas/mathematics/college/3tj6wpi0n5u9prprlbsc6ayeoai6w3lrnl.png)

The first limit converges to 0, since n! asymptotically behaves like nⁿ, so ln(nⁿ/n!) → ln(1) = 0.

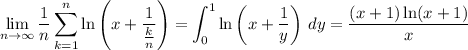

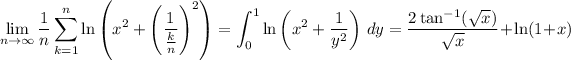

The two remaining sums converge to definite integrals:

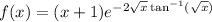

It follows that

![f(x) = \exp\left[x\left(0 + \frac{(x+1)\ln(x+1)}x - (2\tan^(-1)(\sqrt x))/(\sqrt x) - \ln(x+1)\right)\right]](https://img.qammunity.org/2023/formulas/mathematics/college/l392phpvyc6lf67ypru07wrfgsc58yiisd.png)

![f(x) = \exp\left[\ln(x+1) - 2\sqrt x \tan^(-1)(\sqrt x)\right]](https://img.qammunity.org/2023/formulas/mathematics/college/hqtfu10oqvsyp1oh3l36fip1k5njh9rhqy.png)

By computing f'(x) and f''(x), it's easy to show that f'(x) ≤ 0 and f''(x) ≥ 0 for all x > 0. So f(x) is decreasing and f'(x) is increasing, and

• (A) f(1/2) ≥ f(1) is true

• (B) f(1/3) ≤ f(2/3) is false

• (C) f'(2) ≤ 0 is true

• (D) f'(3)/f(3) ≥ f'(2)/f(2) ⟺ f'(3)/f'(2) ≥ f(3)/f(2) ⟺ (something larger than 1) ≥ (something smaller than 1) is true