Answer: D) 1/e but you probably know already

Explanation:

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus part 1:

![\text{Suppose g(x) is continuous on [a,b]} \\\text{Then for all x in [a,b]: }(d)/(dx)\int\limits^x_ag(t)dt=g(x)\text{*}\\\text{In this case }g(x)=e^(-x^2)\text{ which is continuous over }[-\infty,\infty]\text{**}\\\text{So it's continuous at x=1 in particular}. \text{ Set a=1 and }b=\infty\\\text{We see that }(d)/(dx) f(x)=(d)/(dx)\int\limits^x_a {e^(-t^2)} \, dt=e^(-x^2)=g(x)\text{ for all x in }[1,\infty]](https://img.qammunity.org/2022/formulas/mathematics/college/f9kt47c7vzjhpjzlcclifitak9nsbfsnnx.png)

A similar argument where a= -infinity and b=1 gives you d/dx f(x) = g(x) for all x in [-infinity, 1]. Therefore it holds for all x in [-infinity, infinity]

Also, d/dx (x+1) = 1

Also also, f(1)=0 because the bounds become equal

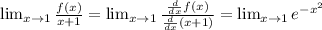

Thus the limit is an indeterminate form of 0/0; this suggests using L'Hopital's Rule

By definition of continuity and the fact that the above g(x) converges at 1, we have

*there's a proof on proofwiki.org that's too long to fit here, but you probably don't need it

**it's 3am, maybe I'll prove it in the morning if I have time lol. Anyway if want to do it yourself, you can use the limit definition of congruence, drag the limit symbol to the exponent -x^2, etc. Or just apply the theorem without checking for continuity. Tell me if you need more detail (or less rambling)