Answer:

y = -3x

Step-by-step explanation:

The equation of the line has the form

y = mx + b

Where m is the slope and b is the y-intercept.

To find the slope, we will use the following equation:

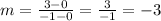

Where (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) are the coordinates of two points in the line. Replacing (x1, y1) = (0,0) and (x2, y2) = (-1, 3), we get

Therefore, the slope is -3.

The equation crosses the y-axis at the origin, so the y-intercept is 0. Then, the equation of the line is

y = -3x + 0

y = -3x

So, the answer is

C. y = -3x